Diet, nutrition and oral health are closely linked. Nutrition is an essential for the growth, development, and maintenance of structures and tissues in the mouth. During periods of rapid cell growth, there can be an irreversible effect on the developing oral tissues if any nutrition deficiency is present. Prior to tooth eruption in the mouth, nutritional status can influence tooth enamel maturation and chemical composition as well as tooth shape and size. Early malnutrition increases a child’s risk to tooth decay in the baby teeth.Throughout life, nutritional deficiencies or toxicities can affect host resistance, healing, oral function, and oral-tissue integrity.

Diet, nutrition and oral health are closely linked. Nutrition is an essential for the growth, development, and maintenance of structures and tissues in the mouth. During periods of rapid cell growth, there can be an irreversible effect on the developing oral tissues if any nutrition deficiency is present. Prior to tooth eruption in the mouth, nutritional status can influence tooth enamel maturation and chemical composition as well as tooth shape and size. Early malnutrition increases a child’s risk to tooth decay in the baby teeth.Throughout life, nutritional deficiencies or toxicities can affect host resistance, healing, oral function, and oral-tissue integrity.

After tooth eruption, the effects of diet on the teeth are local rather than systemic. Dietary factors and eating patterns can worsen or minimize dental decay. Fermentable carbohydrates are essential for the implantation, colonization, and metabolism of bacteria in dental plaque. Factors such as eating frequency and retentiveness of carbohydrates influence the progression of cavities, while foods containing calcium and phosphorus, such as cheese, enhance remineralization of tooth enamel. Frequent intake of acidic foods or beverages can cause tooth enamel erosion.

On the other hand, impaired dental function may lead to poor nutritional health. Older adults with loose or missing teeth, or ill-fitting dentures often reduce their intake of foods that require chewing, such as fresh fruits, vegetables, meats, and breads. When the variety of foods in a diet is reduced, there is greater risk of nutrient inadequacies. Individuals with diabetes mellitus, oral cancer, or depressed immune function may suffer from oral conditions that compromise nutritional status.

Role of nutrition for good teeth and gums

Nutrition plays an important role in the initial growth and development of tissues in the mouth and in their continuous integrity through the lifespan. Optimal nutrition during periods of hard and soft tissue development allow these tissues to reach their optimal potential for growth and resistance to disease. Malnutrition (either over or under-nutrition) during critical periods of cell development can have irreversible effects on developing tissues. Examples of this effect can be seen in the tetracycline staining of teeth and in dental fluorosis. Malnutrition after initial organ and tissue development is usually reversible, but can still compromise tissue regeneration and healing and increase susceptibility to oral diseases. Nutrients for which deficiencies or excesses have been directly associated with oral conditions are protein; energy; vitamins C, A, D; iodine; and fluoride.

Protein/Calorie Malnutrition

Protein is the most abundant organic compound in the body and is required for the synthesis of virtually all body tissues and structures. Proteins account for the structure of DNA, the tensile strength of collagen, and the viscosity of saliva. The normal turnover of tissue in the oral cavity requires a continual supply of nutrients. Thus, any severe deficiency of protein/calorie intake will result in a decrease in cell activity in the gums, as well as elsewhere throughout the body.

In chronically malnourished children, several studies have shown slower teeth eruption and increased tooth enamel solubility, leading to increased risk of tooth decay. Linear hypoplasia (a type of enamel defect whereby there is underdevelopment or incomplete development of enamel tissue) appears to be related to the severity of the malnutrition.

With the exception of the cleansing and diluting effects of saliva, oral defense mechanisms depend on an adequate supply of proteins which includes enzymes and cells involves in immunity.

Food source: Cheese, beans, lean meat and fish.

Minerals

Calcium, in association with vitamin D and phosphorus is essential for proper development and maintenance of mineralized tissues (teeth and alveolar bone). A deficiency of these nutrients during critical phases of tooth development in children results in hypomineralization of developing teeth (a condition whereby the teeth have less mineralised tissue), and possible delayed eruption of teeth.

Food source: Milk and milk products, sardines, clams, turnip and mustard greens, broccoli.

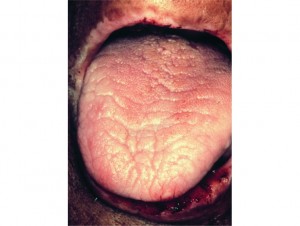

Iron is of interest since iron deficiency is the most common deficiency in the United States. Iron deficiency anemia can manifest in the mouth by the paleness of oral tissues, especially the tongue.

Food source: Organ meats, clams, oysters, legumes, enriched and/or whole grain cereals and breads.

Zinc regulates function in inflammation by inhibiting the release of lysosomal enzymes and histamines. A zinc deficiency can inhibit collagen formation and reduce cell-mediated immunity.

Food source: Wheat germ, oysters, beef liver, dark meat of poultry.

Vitamins

Vitamin A is essential for the development and continued integrity of all body organs and tissues, including the tissues in the mouth. Vitamin A helps in maintenance of healthy mucous membrane, formation of tooth tissues and maintains salivary flow in the mouth.

In vitamin-A deficiency, cell activity is impaired and could result in defective tissue formation and impaired healing. Vitamin-A deficiency also can affect tissue response to bacterial infection, mucosal immunity, parasitic and viral infection, natural killer-cell activity, and phagocytosis.

Food source: Present only in animal foods; beef liver is an excellent source. Beta carotene: carrots, melon, squash, sweet potato, spinach

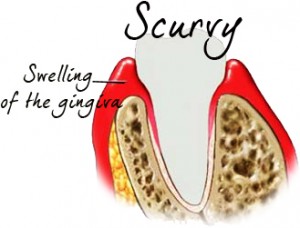

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is essential to oral health. It prevents all forms of inflammation of the gums. Deficiency can lead to scurvy and poor collagen formation and wound healing. In the mouth these include spontaneous bleeding of gums, loosening and falling off of teeth, loose gum tissues, and impaired wound healing.

Food source: Citrus fruits, papaya, broccoli, potato, strawberries.

The B-complex vitamins primarily function as co-enzymes in energy metabolism. B-complex vitamins are found widely in foods, and usually together. With the exception of B12 in the elderly and folic acid in pregnant women, deficiencies of single B vitamins are uncommon. Oral signs and symptoms of B-complex vitamin deficiencies include cracks in the corners of the mouth (cheilosis), inflammation, burning, redness, pain and swelling of the tongue.