Prophylaxis is the prevention of an occurrence. In surgery this is usually infection or thromboembolism (Occlusion of a blood vessel by an embolus that has broken away from a blood clot formed within a blood vessel). Prophylaxis used to prevent the occurrence of bacterial infection is quite different from treating an established infection.

There are two broad categories of individuals requiring dental antibiotic prophylaxis:

- those who have it to prevent a minor local bacteremia (presence of bacteria in the bloodstream) causing a serious infection out of all proportion to the procedure, for example the immunocompromised.

- those who receive it to prevent local septic complications of the procedure, for example wisdom tooth removal.

The American Heart Association (AHA) published its first guidelines in 1955 recommending that patients with certain heart conditions take antibiotics shortly before dental treatment. This was done with the belief that antibiotics would prevent infective endocarditis (IE). The guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis were updated in 1990 and most recently in 1997 with recommendations that most of these patients no longer need short-term antibiotics as a preventive measure before their dental treatment.

The AHA antibiotic guidelines are followed by most dental practitioners, but it is not unusual to find certain changes in dosages or medications made by particular doctors.

Principles of antibiotic prophylaxis

The regimen should be short, high dose, and appropriate to the potential infecting organism. The aim is to prevent pathogens establishing themselves in surgically traumatized or otherwise at-risk tissues; therefore the antimicrobial must be in those tissues prior to damage or exposure to the pathogen. It must not however be present too long before this, as there is then a risk of development of drug-resistant bacteria and damage to commensal organisms.

What is infective endocarditis?

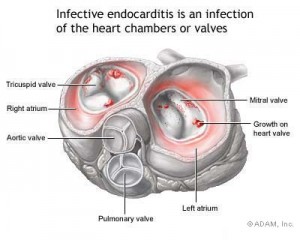

Infective endocarditis (IE), previously referred to as bacterial endocarditis, is a rare but dangerous potentially lethal infection, predominantly affecting heart valves. Platelets and fibrin deposits accumulate at sites where there is turbulent blood flow over damaged valves (nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis. These sterile vegetations can thereafter readily be infected during bacteremias, resulting in inflammation and deformation of the heart known as infective endocarditis. Infective carditis results from two main predisposing factors – bacteremia and a cardiac lesion where there is turbulent blood flow.

Causative factors of infective endocarditis

- Numbers of bacteria entering the blood

- Ability of bacteria to adhere to endocardium (The membrane that lines the cavities of the heart and forms part of the heart valves)

- Host factors increasing susceptibility

- Local lesions

- Congenital

- Prosthetic heart valves

- Other heart disease

- Protective factors

- Antimicrobial chemotherapy

Infective endocarditis symptoms and signs

The signs and symptoms are highly variable. In a previously healthy individual who acquired endocarditis, the likely picture would be that 3 or 4 weeks after a dental operation, there is subtle onset of low fever and mild physical discomfort.

Pallor (anemia) or light (café-au-lait) pigmentation of the skin, joint pains and enlargement of the liver and spleen are typical. The main effects of endocarditis are:

- progressive heart damage,

- infection or embolic damage of many organs, especially the kidneys,

- immune complex formation from the antigens and resultant antibodies, which can lead to inflammation of a blood vessel, arthritis and kidney damage,

- without treatment, infective endocarditis may be fatal in about 30%.

How likely will infective endocarditis occur from dental treatment?

In statistical terms, the chance of dental extractions causing infective endocarditis, even in patient with valvular disease, may possibly be as low as 1 in 3,000. Infective endocarditis only rarely follows dental procedures and it is not proven that antimicrobial prophylaxis effectively prevents endocarditis. There is always a risk of adverse reactions to the antimicrobial (such as anaphylaxis) which can approach 5%. Furthermore hearts of those at risks are already often exposed to bacteria from the mouth, which can enter their bloodstream during basic daily activities such as brushing or flossing.

Individuals at risk for endocarditis should receive intensive preventive dental care, to try and minimize the need for dental intervention. Prophylaxis should be given for dental procedures that disturb the bacteria in periodontal pockets, since this provides a good chance of precipitating infective endocarditis in susceptible individuals.

Do I need antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment?

The AHA guidelines say individuals who have taken prophylactic antibiotics routinely in the past but no longer need them include people with:

- mitral valve prolapse

- rheumatic heart disease

- bicuspid valve disease

- calcified aortic stenosis

- congenital heart conditions such as ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

To be continued in Part 2