In Anatomy, the Curve of Spee (called also von Spee’s curve or Spee’s curvature) is defined as the curvature of the mandibular occlusal plane beginning at the tip of the lower cuspid and following the buccal cusps of the posterior teeth, continuing to the terminal molar. According to another definition Curve of Spee is an anatomic curvature of the occlusal alignment of teeth, beginning at the tip of the lower canine, following the buccal cusps of the natural premolars and molars, and continuing to the anterior border of the ramus. Ferdinand Graf von Spee, German embryologist, (1855–1937) was first to describe anatomic relations of human teeth in the sagittal plane. Continue reading

Author Archives: chzechze

Self ligating braces Part 3

Secure archwire engagement and low friction as a combination

Other bracket types—most notably Begg brackets—have achieved low friction by virtue of an extremely loose fit between a round archwire and a very narrow bracket, but this is at the cost of making full control of tooth position correspondingly more difficult. Some brackets with an edgewise slot have incorporated shoulders to distance the elastomeric from the archwire and, thus, reduce friction, but this type of design also produces reduced friction at the expense of reduced control. A deformable elastomeric ring cannot provide and sustain sufficient force to maintain the archwire fully in the slot without actively pressing on the archwire to an extent that increases friction. Continue reading

Self ligating braces Part 2

Advantages of self-ligating brackets

These advantages apply in principle to all self-ligating brackets, although the different makes vary in their ability to deliver these advantages consistently in practice:

more certain full archwire engagement;

low friction between bracket and archwire;

less chairside assistance;

faster archwire removal and ligation. Continue reading

Self ligating braces Part 1

Self-ligating brackets have an inbuilt metal labial face, which can be opened and closed. Brackets of this type have existed for a surprisingly long time in orthodontics— the Russell Lock edgewise attachment being described by Stolzenberg in 1935. Many designs have been patented, although only a minority have become commercially available. Self-ligating braces are defined as “a [dental] brace, which utilizes a permanently installed, moveable component to entrap the archwire”. Self-ligating braces may be classified into two categories: Passive and Active. Continue reading

Implantable devices as orthodontic anchorage Part 3

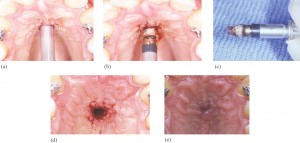

Palatal Implants

One of the limitations of using implants for orthodontic anchorage is having adequate bone. Conventional root-form implants require adequate thickness of bone for placement, thus limiting their use to edentulous areas. Several authors have reported the midsagittal area of the hard palate as a suitable site for a short implant. Continue reading

One of the limitations of using implants for orthodontic anchorage is having adequate bone. Conventional root-form implants require adequate thickness of bone for placement, thus limiting their use to edentulous areas. Several authors have reported the midsagittal area of the hard palate as a suitable site for a short implant. Continue reading

Implantable divices as orthondontic anchorage Part 2

The high level of stability gained from the types of implants placed in retromolar or midpalatal regions is derived largely from the fact that the implants are osseointegrated. Initial concerns about disruption of osseointegration by orthodontic loading were proven to be unfounded by several studies. Continue reading

Implantable devices as orthodontic anchorage Part 1

Over the past 20 years dentistry has seen a dramatic increase in the use of dental implants. What was once an “experimental†or unproven treatment modality is now supported by an extensive research base. The vast majority of dental implant research is centered around the use of endosseous implants for replacement of missing teeth. Recently, the application of implants for use in other specialties has been explored. Previously, the use of dental implants within the specialty of orthodontics was limited to integration of implants into treatment plans strictly to facilitate tooth replacement. The orthodontic treatment that has traditionally been involved in treatment plans including dental implants has been limited to creating space or aligning roots for subsequent placement of implants. The use of dental implants as a direct adjunct to orthodontic treatment has been more limited until recently, but the potential exists for implants to play an important role in enhancing successful treatment outcomes. Continue reading

Skeletal and dental changes brought by Frankel appliance Part 2

Whether or not there is an increase in size or acceleration of growth of the mandible is one of the major controversies in functional appliance therapy. Although many researchers have claimed that the FR causes extra mandibular growth, this study showed that there were no significant differences between the FR and control groups as far as mandibular movement is concerned, the mean FR movement being 4.1 mm, standard deviation 3.0 mm; the control 5.0 mm, and standard deviation 2.6 mm. As the 5.0-mm change in the control was due to normal growth, it can be assumed that the 4.1-mm change in the FR group was no more than normal growth rather than any effect of the appliance. The maximum value seen in the control was 14.2 mm and for the FR it was 12.8 mm; again, because this change in the controls was due to normal growth it must be assumed that even the maximum FR change was no more than normal growth change. That the size of the mandible is unaffected with the FR is supported by evidence from Creekmore and Radney, and Hamilton et al., who found no significant differences between FR and untreated patient groups. Continue reading

Skeletal and dental changes brought by Frankel appliance Part 1

Functional appliances have been used for many years in the treatment of Class II division 1 malocclusions, the selection of which varies with the type of skeletal and dental anomaly, the growth pattern, and the operator’s preference. Continue reading

Cracked tooth

With their more sophisticated procedures, dentists are helping people keep their teeth longer. Because people are living longer and more stressful lives, they are exposing their teeth to many more years of crack-inducing habits, such as clenching, grinding, and chewing on hard objects. These habits make our teeth more susceptible to cracks. Continue reading