Odontology, the science of using dental information to identify a deceased person, began as early as the first century A.D. Since then, this field of study has grown to be recognized worldwide by organizations such as the American Board of Forensic Odontology. It is useful both in convicting criminals in court and in identifying victims of natural disasters.

Ancient History and the Middle Ages

The earliest record of an individual being identified based on dental examination dates back to 66 A.D., when Nero’s mother accepted the head of Lollina Paulina as proof of his death based on the discoloration of his teeth. The early practice of odontology is mentioned again in historic information from the Middle Ages. This time, dental records were used to identify John Talbot, a soldier who was killed in the Battle of Castillon.

Early American History

The first known use of odontology in the New World occurred when dentist and revolutionary Paul Revere identified the otherwise unrecognizable body of Dr. Joseph Warren based on a dental bridge he had constructed for him two years prior. Odontological evidence was first accepted in court about 75 years later in the Webster-Parkman case, during which the jury was presented with remnants of dental fillings from the victim’s dismembered body. The first treatise on forensic odontology was written by Dr. Oscar Amoedo in 1898 and was entitled L’Art Dentaire en Medicine Legale. Dr. Oscar is also known as father of Forensic Odontology.

Mid-1900s

The practice of odontology made some of its most significant advances during the mid-twentieth century. Two odontologists (Welty and Glasgow) developed a system in which dental records could be analyzed quickly by a system of cards used on a computer. This invention significantly advanced the odontological process, making it both more accurate and easier to use. This process was then further refined as it was used to identify remains in a number of large-scale disasters. Teeth are highly resistant to destruction and decomposition, so dental identification can also be made under extreme circumstances. It was used on Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun at the end of World War II, the New York City World Trade Center bombing, the Waco Branch Davidien siege, and numerous airplane crashes and natural disasters.

Individualization from dental radiographs is based upon several factors, the most important being the ability to locate a source of known dental or medical radiographs, which clearly document unique points of identification. As has been previously stated, it is also dependent upon the survivability of dental structure for post mortem radiography. Further, it is also dependent upon deriving a presumptive identification of the fatality from other investigative means; i.e., flight manifests, personal effects, or other circumstantial evidence. Unlike a central repository for automated fingerprint analysis, dental records must be derived individually.

Once obtained, even a single dental radiograph can yield multiple points of comparison. When one considers that an individual has the potential for having thirty-two teeth, each tooth having a top and four sides and each of these five surfaces being virgin or restored with one or more of several types of dental materials, the probability of establishing an identification is extremely high. When factors such as an extraction pattern, the presence of anatomic anomalies or pathology is added, the probability of the dental characteristics becoming unique can be established.

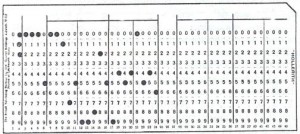

In 1937 in Chantilly, a murder was convicted on the evidence of the bite marks that the victim inflicted during her struggle for life. In 1946 Welty and Glasgow devised a system in which as many as 500 cards with dental data could be sorted in one minute by a computer. The following year Taltersall wrote that he advocated the Hollerith system of punch cards and thought this would be very beneficial in compiling dental data. The scope of this specialty has expanded since the end of the 1939-1945 was due to the quarter intensity of international traffic coincident are destroyed and often Internationally there is an obvious growth of interest in this field there are organizations such as the Scandinavian society of Forensic Odontology, the Federation Dentaire International. The Canadian Society of Forensic Sciences, the American society of Forensic Odontology and the American Academy of Forensic Sciences.

Recent Uses for Odontology

Odontology has been used to recognize victims of events such as the World Trade Center attacks in 2001, where teeth were often the only part of the body that survived the destruction. While fingerprinting is still the preferred method of identifying victims, odontology has proven to be very helpful in many cases. It has been recognized officially by the American Board of Forensic Odontology. The U.S. has a fairly well-developed system of dental records system (the Universal System), so it’s not surprising to find it used for the identity of remains or “Jane Doe” victims. You can also tell age solely by analysis of teeth — the Gustafson method (looking for six signs of wear) or the Lamendin method (looking at transparency of roots).

Need for Future Advances

The practice of odontology has room for advancement on several levels. For example, dental records are only useful when scientists have a reasonable guess about who the teeth may belong to. For example, forensic specialists who wish to identify the remains of a body from a plane crash must first narrow down the list of victims from the names of people who boarded the plane. As this science improves, forensic scientists may be able to compare dental records in the same way they compare fingerprints.