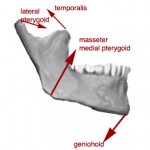

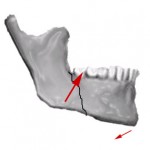

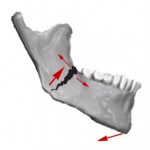

The effect of muscle action on the fracture fragments is important in classification of mandibular angle and body fractures. Angle fractures may be classified as (1) vertically favorable or unfavorable and (2) horizontally favorable or unfavorable. The muscles attached to the ramus (masseter, temporal, medial pterygoid) pull the proximal segment upward and medially and the symphysis of the mandible is displaced inferiorly and posteriorly by the pull of the digastric, geniohyoid, and genioglossus muscles.

When the fractures are vertically and horizontally unfavorable, the fragments tend to be displaced.

Conversely, these same muscles tend to stabilize the bony fragments in horizontally and vertically favorable fractures.

Condylar fractures are classified as extracapsular, subcondylar, or intracapsular. The lateral pterygoid tends to cause anterior and medial displacement of the condylar head. Five types of condylar fractures are described in order of increasing severity:

- Type I is a fracture of the neck of the condyle with relatively slight displacement of the head. The angle between the head and the axis of the ramus varies from 10-45°.

- Type II fractures produce an angle from 45-90°, resulting in tearing of the medial portion of the joint capsule.

- Type III fractures are those in which the fragments are not in contact, and the head is displaced medially and forward. The fragments are confined within the area of the glenoid fossa. The capsule is torn, and the head is outside the capsule.

- Type IV fractures of the condylar head articulate on or in a forward position with regard to the articular eminence.

- Type V fractures consist of vertical or oblique fractures through the head of the condyle.

Indications

The indications for closed versus open reduction have changed dramatically over the last century. The ability to treat fractures with open reduction and rigid internal fixation (ORIF) has dramatically revolutionized the approach to mandibular fractures.

Traditionally, closed reduction (CR) and ORIF with wire osteosynthesis have required an average of 6 weeks of immobilization by maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) for satisfactory healing. Difficulties associated with this extended period of immobilization include airway problems, poor nutrition, weight loss, poor hygiene, phonation difficulties, insomnia, social inconvenience, patient discomfort, work loss, and difficulty recovering normal range of jaw function. In contrast, rigid and semirigid fixation of mandible fractures allow early mobilization and restoration of jaw function, airway control, improved nutritional status, improved speech, better oral hygiene, patient comfort, and an earlier return to the workplace.

Schmidt et aland Shetty et alperformed financial analysis comparing patients treated with closed reduction and MMF with those treated with ORIF, and found, at least within the patient population at risk for mandible fractures, that the closed treatment was more cost-effective.

Indications for closed reduction

- Nondisplaced favorable fractures: Open reduction carries an increased risk of morbidity, thus use the simplest method to reduce and fixate the fracture.

- Grossly comminuted fractures: Generally, these are best treated by closed reduction to minimize stripping of the periosteum of small bone fragments.

- Fractures in children involving the developing dentition: Such fractures are difficult to manage by open reduction because of the possibility of damage to the tooth buds or partially erupted teeth.A special concern in children is trauma to the mandibular condyle.The condyle is the growth center of the mandible, and trauma to this area can retard growth and cause facial asymmetry. Early mobilization (7-10 d of intermaxillary fixation) of the condyle is important.If open reduction is necessary because of severe displacement of the fracture, the use of resorbable fixation or wires along the most inferior border of the mandible may be indicated.

- Coronoid fractures: These fractures usually require no treatment unless impingement on the zygomatic arch is present.

- Treatment of condylar fractures: This is one of the more controversial topics in maxillofacial trauma.Indications for open reduction are discussed below. If condylar fractures do not fall within this criteria, they can be treated with closed reduction for a period of 2-3 weeks to allow for initial fibrous union of the fracture segments. If the condylar fracture is in association with another fracture of the mandible, treat the noncondylar fracture with ORIF, and treat the condylar fracture with closed reduction.

Indications for open reduction

- Displaced unfavorable fractures through the angle of the mandible: Often, the proximal segment is displaced superiorly and medially and requires an open technique for proper reduction.

- Severely atrophic edentulous mandibles: These have little cancellous bone remaining and minimal osteogenic potential, and fracture healing may be delayed. Ellis and Price advocate an aggressive protocol of ORIF with rigid fixation and acute bone grafts.They demonstrated no complications with this approach, despite the advanced age and medical comorbidities of this patient population.