A surgical drain is a tube used to remove pus, blood or other fluids from a wound. Drains inserted after surgery do not result in faster wound healing or prevent infection but are sometimes necessary to drain body fluid which may accumulate and in itself become a focus of infection. The routine use of drains for surgical procedures is diminishing as better radiological investigation and confidence in surgical technique have reduced their necessity. It is felt now that drains may hinder recovery by acting as an ‘anchor’ limiting mobility post surgery and the drain itself may allow infection into the wound. In certain situations their use is unavoidable. Drains have a tendency to become occluded or clogged, resulting in retained fluid that can contribute to infection or other complications. Thus efforts must be made to maintain and assess patency when they are in use. Once a drain becomes clogged or occluded, it is usually removed as it is no longer providing any benefit.

Drains may be hooked to wall suction, a portable suction device, or they may be left to drain naturally. Accurate recording of the volume of drainage as well as the contents is vital to ensure proper healing and monitor for excessive bleeding. Depending on the amount of drainage, a patient may have the drain in place one day to weeks. Signs of new infection or copious amounts of drainage should be reported to the health care provider immediately. Drains will have protective dressings that will need to be changed daily/as needed.

Drains may be:

1 superficial, i.e. in the wound;

2 deep:

(a) intraperitoneal, e.g. covering an intestinal anastomosis,

(b) in a hollow organ or duct, e.g. a T-tube in the bile duct,

(c) in an abnormal channel, e.g. a fistula,

(d) to drain a deep cavity, e.g. an abscess or haematoma

In addition drains may be:

1 open, i.e. draining into a dressing or bag open to the air:

2 closed, i.e. draining into a sterilized air-right tube and container. The drainage system may be:

(a) on tree drainage, e.g. drainage of ascites by gravity;

(b) on suction, e.g. Redivac drains:

(c) controlled by a one-way valve, e.g. an underwater sea or chest drains .

Types of drains and their uses

Open drains

Corrugated rubber drain. Rubber causes a tissue reaction and the drain track caused by this material persists longer than when inert materials arc used. The drain is fixed by a suture at the end of the wound and a safety pin must he placed through the end to prevent the drain slipping inwards. Corrugated rubber drains can be used either for the wound or for deep drainage.

Yates‘ drain. This is a corrugated drain made of a series of capillary tubes joined side to side. It is generally made of polyethylene which is less reactive than rubber. The drain site, therefore, tends to close more quickly once the drain has been removed. Its uses are similar to corrugated rubber drains and it is secured as described above.

Penrose drain. This is a drain fashioned out of thin-walled rubber tubing and a gauze wick is threaded through the centre of the tube. Fluid can then either drain down the track once the tube is removed or through the centre whilst it is in place.

Closed drains

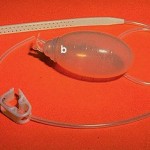

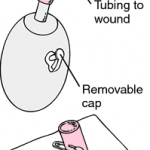

Redivac drain. This is a fine tube with many holes at the end, which is attached to an evacuated glass bottle providing suction. It is used to drain blood beneath the skin, e.g. after mastectomy or thyroidectomy, or from deep spaces, e.g. around a vascular anastomosis.

‘Shirlry’ wound drainage. This is a suction drain with an intake tube supplying air to the bottom of the main tube. This allows continuous suction and the flow of air prevents the tube getting block

General guidance

- If active, the drain can be attached to a suction source (and set at a prescribed pressure).

- Ensure the drain is secured (dislodgement is likely to occur when transferring patients after anaesthesia). Dislodgement can increase the risk of infection and irritation to the surrounding skin.

- Accurately measure and record drainage output.

- Monitor changes in character or volume of fluid. Identify any complications resulting in leaking fluid (particularly, for example, bile or pancreatic secretions) or blood.

- Use measurements of fluid loss to assist intravenous replacement of fluids.

Removal

Generally, drains should be removed once the drainage has stopped or becomes less than about 25 ml/day. Drains can be ‘shortened’ by withdrawing them gradually (typically by 2 cm per day) and so, in theory, allowing the site to heal gradually. Usually drains that protect postoperative sites from leakage form a tract and are kept in place longer (usually for about a week).

- Warn the patient that there may be some discomfort when the drain is pulled out.

- Consider the need for pain relief prior to removal.

- Place a dry dressing over the site where the drain was removed.

- Some drainage from the site commonly occurs until the wound heals.

- When to remove:

- Drains left in place for prolonged periods may be difficult to remove.

- Early removal may decrease the risk of some complications, especially infection.