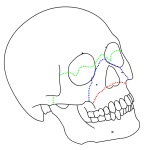

Le Fort fractures (also spelled as LeFort fractures) are types of facial fractures involving the maxillary bone and surrounding structures in a usually bilateral and either horizontal, pyramidal or transverse way. LeFort fractures are classic in facial trauma. The Le Fort fracture was named after French surgeon René Le Fort (1869–1951), who described them in the early 20th century.

The maxilla represents the bridge between the cranial base superiorly and the dental occlusal plane inferiorly. Its intimate association with the oral cavity, nasal cavity, and orbits and the multitude of structures contained within and adjacent to it make the maxilla a functionally and cosmetically important structure. Fracture of these bones is potentially life-threatening as well as

disfiguring.Timely and systematic repair of these fractures provides the best chance to correct deformity and prevent unfavorable sequelae.

Etiology

Maxillary fractures often result from high-energy blunt force injury to the facial skeleton. Typical mechanisms of trauma include motor vehicle accidents, altercations, and falls.With increased legislation requiring seat belt use, injuries from driver impact with the steering wheel have shifted from chest trauma to facial trauma.

Presentation

History

Information regarding the mechanism of the injury may assist in determining a diagnosis. In particular, knowing the magnitude, location, and direction of the impact is helpful. High-energy trauma should cause concern about other possible concomitant

injuries. A history of mental status changes or loss of consciousness should cause concern regarding intracranial injury. The presence of any functional deficiencies, such as those related to airway, vision, cranial nerves, occlusion, or hearing, may provide clues to fracture location and resultant adjacent nonosseous injury.

Physical examination

Evaluation of the maxilla and facial bones should be undertaken only after the patient has been fully stabilized and life-threatening injuries have been addressed. In particular, airway considerations and intracranial injuries must take immediate priority.

In general, patients with facial fractures have obscuration of their bony architecture with soft tissue swelling, ecchymoses, gross blood, and hematoma. Nonetheless, observation alone may be informative. Focal areas of swelling or hematoma may overlie an isolated fracture. Periorbital swelling may indicate Le Fort II or III fractures. A global posterior retrusion of the mid face creates a flattened appearance of the face. The so-called dish-face or pan-face deformity may occur after an extensive Le Fort II or Le Fort III fracture. The maxillary segment is displaced posteriorly and inferiorly. This may cause premature contact of the molar teeth, resulting in an anterior open bite deformity. In severe cases, the upper airway may be compromised. In such a situation, disimpaction forceps may need to be placed into the nasal floor and hard palate to pull the bony segment forward to restore airway patency.

The face and cranium should be palpated to detect for bony irregularities, step-offs, crepitus, and sensory disturbances. Mobility of the mid face may be tested by grasping the anterior alveolar arch and pulling forward while stabilizing the patient with the other

hand. The size and location of the mobile segment may identify which type of Le Fort fracture is present. If only an isolated segment of bone is mobile, a small alveolar or nasofrontal process chip fracture may be present. With high-impact force, the maxilla may be comminuted or impacted, in which case the bony framework is displaced or crushed but immobile.

A thorough nasal and intraoral examination should be completed. The nasal bones are typically quite mobile in Le Fort II fractures, along with the rest of the pyramidal free-floating segment. Intranasal examination may reveal fresh or old blood, septal hematoma, or cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. The intraoral examination should assess occlusion, overall dentition, stability of the alveolar ridge and palate, and soft tissue. Finger palpation of the maxillary contour intraorally may provide additional information about the integrity of the nasomaxillary buttress, anterior maxillary sinus wall, and zygomaticomaxillary buttress.

During examination of the eyes and orbit, search for integrity of the orbital rims, orbital floor, vision, extraocular motion, position of the globe, and intercanthal distance. Unlike Le Fort II fractures, Le Fort III fractures are associated with lateral rim and

zygomatic breaks. Visual changes may signify a disturbance of the optic canal, problems within the globe or retina, or other neurologic lesions. Disturbances of extraocular motion or enophthalmos may signify a blowout in the orbital floor. An increased intercanthal distance implies displacement of the frontomaxillary or lacrimal bones or avulsion of the medial canthal ligament. For extensive involvement of the orbit or globe, consultation with an ophthalmologist is appropriate.

Tools that may assist the examiner in the evaluation of maxillofacial trauma include a headlamp or mirror, tongue blades, a suction device, a nasal speculum, an otoscope, and a ruler. Early photographs may be helpful in preoperative planning and patient

counseling.