Continued from Part 1

Melanin pigmentation – acquired causes

Acquired melanosis of the oral mucosa may be a manifestation of systemic disease, cancer or of a simple local disorder. It is an important sign indicating the need for careful investigations of the individual.

The anterior pituitary gland releases melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), which increases melanin production. Melanin pigmentation thus increases under hormonal stimulation, either by MSH, or in pregnancy, or rarely due to the action of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), the molecule of which is similar to MSH, or under the influence of other factors (for example smoking).

The association of oral pigmentation with Addison’s disease (hypoadrenalism) is well recognized and may be the initial manifestation of adrenal insufficiency. Adrenal sufficiency results in elevated secretion of ACTH by the pituitary gland, the melanocyte-stimulating properties of the heptapeptide core probably being responsible for the pigmentation. The pigmentation is most common in areas subjected to chewing trauma, especially the cheeks, but can involve any part of the oral mucosa. Oral hypermelanosis may also be seen in patients with HIV infection.

Nelson syndrome is a rare condition caused by ACTH overproduction in response to surgical removal of one or both adrenal glands, usually for breast cancer.

ACTH-producing tumors may induce brown pigmentation, particularly of the soft palate, and may be an oral manifestation of a rare ACTH-producing neoplasm, such as bronchogenic carcinoma.

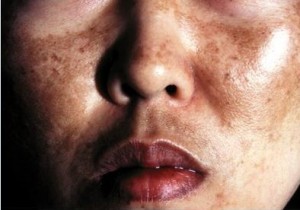

Melanic pigmentation is an associated feature of some hyperkeratoses, giving the lesions a dusky or grayish hue, and less commonly of some other chronic inflammatory mucosal disease. In many individuals with pigmented hyperkeratosis smoking appears to be an important causative factor. An association between smoking, pigmentation of the soft palate, and pulmonary disease, especially bronchogenic carcinoma has also been shown. The pigmentation is presumably a reaction of melanocytes to chronic irritation and there may also be some associated dysfunction in the transfer and/or uptake of melanin from melanocytes to keratinocytes. Chronic inflammation can result in melanin drop-out, especially in individuals with pigmented skin. Similar changes may be seen in lichen planus as a result of basal cell degeneration and may persist after the lesions have healed.

Drug-induced melanic pigmentation of the oral mucosa is rare, but may be seen in some individuals taking various cytostatic agents and may also be produced by progestogens in oral contraceptives. Pigmentary changes, especially of the hard palate, may be seen in individuals taking anti-malarial drugs. The nature of this pigment is uncertain but melanin may be involved. Oral pigmentation has also been reported in individuals taking minocycline, a tetracycline derivative widely used for the treatment of acne. As with other tetracyclines the drug may also be incorporated in and cause discoloration of bones and teeth.

Occasionally, individuals present with single, or less frequently multiple, pigmented macules of the oral mucosa which cannot be classified histologically into any of the recognized types of melanotic lesion and for which no local or systemic cause can be found. Melanotic macules are flat and mostly smaller than 1 cm. They occur more often in women than in men and usually present around 40 years of age. The vermillion border of the lower lip, gums and cheek mucosa are the commonest sites. The term ‘idiopathic oral melanotic macule’ has been applied to this lesion but it is also referred to as an oral freckle (ephelis). The lesion is not associated with increase in the number of melanocytes or with melanocytic atypia. It has no sinister connotations.

Primary malignant melanoma of the oral mucosa is rare but may arise in apparently normal mucosa or in a pre-existent pigmented nevus, usually in the palate or upper gums. Features suggestive of cancer include rapid increase in size, change in color, ulceration, pain, the occurrence of satellite pigmented spots or regional lymph node enlargement.

Kaposi sarcoma is caused by virus HHV-8, which is transmitted sexually, often as a co-infection with HIV. It presents initially a symptomless red, blue or purple macule which progresses to papules, nodules or ulcers and may become painful. It occurs especially at the hard/soft palate junction or the upper front gums.

Other endogenous pigments

Oral pigmentation due to other endogenous substances is uncommon apart from transitory discoloration caused by blood breakdown products in a localized swelling filled with blood and the yellowish hue produced by bilirubin in individuals with jaundice.

Pigmentation associated with disturbances of iron metabolism is seen in the rare disorder, hemochromatosis. Hemosiderin is deposited in many organs and tissues and there is also pigmentation of the skin and oral mucosa. Classically the pigmentation produces coppery or bronze discoloration of skin and is chiefly due to melanin, although hemosiderin is also deposited. The serious manifestations are due to deposition of hemosiderin in the heart muscle, liver and pancreas.

Management of mouth pigmentation

Management is of the underlying condition. Excision biopsy of isolated hyperpigmented lesions is often recommended to exclude cancer, because of the cancerous potential of some (particularly the junctional nevus) and for cosmetic reasons. This is particularly important if the lesions are raised or nodular or have clinical features as above seriously suggestive of being malignant melanoma.