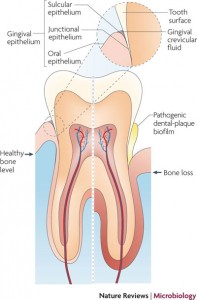

With these concepts in mind, let us review the histology of the periodontal pocket, especially in the area of tissue destruction and healing after the periodontal therapy instituted. The periodontal pocket is described as one which occurred with destruction of the supporting periodontal tissues. Progressive pocket deepening leads to destruction of the supporting periodontal tissues and loosening and exfoliation of the teeth. The suprabony pockets are those which the bottom of the pocket is coronal to the underlying alveolar bone. The infrabony pockets are those which the bottom of the pocket is apical to the level of the adjacent alveolar bone and the lateral pocket wall lies between the tooth surface and the alveolar bone.

Pocket formation starts as an inflammatory change in the connective tissue wall of the gingival sulcus caused by the bacterial plaque. Gingival fibers became degenerate, and the area of the destroyed collagen fibers develops just apical to the junctional epithelium. The coronal portion of the junctional epithelium detaches from the root as the apical portion migrates. Thus the initial deepening of the pocket has been described as occurring between the junctional epithelium and the tooth, or within the junctional and the tooth. During the healing of the periodontal, cells from four different areas compete for repopulation of the pocket. They are: oral epithelium, gingival connective tissue, bone, and periodontal ligament. If the oral epithelium arrives the tooth surface before all other tissues, the result will be long junctional epithelium. If the cells from the gingival connective are first to repopulate the area, the result will be fibers parallel to the tooth surface and remodeling of the alveolar bone, with no attachment to the cementum. External resorption may or may not occur. If bone cells are allowed to repopulate the area, root resorption and ankylosis may occur. Finally, when only the cells from the periodontal ligament proliferate coronally is there new formation of cementum and periodontal ligament. Thus in the last case, the ultimate goal of regeneration and new attachment has been achieved.

In the normal circumstance, the cell of oral epithelium almost always is the first to repopulate the area, thus the common result after the conservative treatment of periodontal therapy would be the establishment of long junctional epithelium. Whereas when the more aggressive or surgical therapy are used such as in the case of guided tissue regeneration (GTR) or guided bone regeneration (GBR), oral epithelium downgrowth is prevented, which allows cells of the periodontal ligament to repopulate the area, aiming to achieve new attachment with osseous regeneration.

Orban in 1948 pointed out that the reattachment of the epithelium always apically from the deepest point of the epithelial attachment. This statement is no longer valid since it negates the repair or regeneration of a tooth/soft tissue interface at any site of a previously existing pocket. To understand fully the concept of new attachment, reattachment, one must examine the histologic evidence of healing following surgical periodontal therapy at two crucial sites, namely, in the area apical to the crest of the alveolar bone (infrabony pocket) and in the area of the supra crestal tissue: the epithelium/connective tissue/tooth wall unit. Further, we will clarify whether healing at these two areas represent repair or regeneration phenomenon. Taylor and Campbell in 1972 suggested a dynamic attachment in which newly proliferated epithelial cells near cervix attach themselves to the tooth and migrate occlusally along its surface. The connective tissue, in its healing, remodels and creates a new margin occlusal to the initial excision. Thus this phenomenon is term “creeping†reattachment. This concept overturns the statement made by Orban as described above. The reattachment did occur above the deepest point of the epithelial attachment. The remodeling of the gingival margin or papilla produced a small gain in an occlusal direction. When the inverse bevel was used, there is also a long connective tissue interfaced exposed. Since connective tissue insertion supracrestally almost never occurred, clinical healing can only be the result of epithelial adherence of the epithelium covering the connective tissue to the root, ergo, a long junctional adhesion, or a long junctional epthithelial adhesion and some collagen adhesion to the root. Next we will explore the connective tissue/tooth adherence.

A common observed response in this case is the alignment of fibers parallel to the root in the area immediately below the most apical position of the junctional epithelium. This is where contact inhibition of epithelial downgrowth. Supracrestal fibers filled the infraosseous defect and adhered to tooth surface. It is possible that the supracrestal healing response following flap surgery is a connective tissue adherence over a limited space immediately apical to the junctional epithelial adherence.

Another mode of healing via connective tissue/tooth attachment is the fiber splicing, or “renewed attachment is the result from linkage and splicing of new and old collagen”. The collagen fibrils of the new connective tissue align in a close opposition to the exposed root surface fibrils. This is the same phenomenon as seen in reimplanted teeth into the socket. This process, since it involves the reattachment or splicing between the “old†fiber ends from the tooth surface and the “new†fibers from the healing flap wound edge, is better classified as “repair†rather than regeneration.

Another mode of healing via connective tissue/tooth attachment is the fiber splicing, or “renewed attachment is the result from linkage and splicing of new and old collagen”. The collagen fibrils of the new connective tissue align in a close opposition to the exposed root surface fibrils. This is the same phenomenon as seen in reimplanted teeth into the socket. This process, since it involves the reattachment or splicing between the “old†fiber ends from the tooth surface and the “new†fibers from the healing flap wound edge, is better classified as “repair†rather than regeneration.