Diagnosis

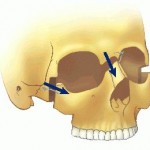

Diagnosis is made based on physical exam findings with confirmation by axial CT. The patient is taken for radiography of the head and neck then after obvious fracture signs the patient is taken to CT scan for more specific anatomic information. To qualify for LeFort Fractures the pterygoid plates must be involved. These are seen posterior to the maxillary sinuses on axial CT and inferior to the orbital rim on coronal slices. Also, the palate is usually mobile on physical exam.

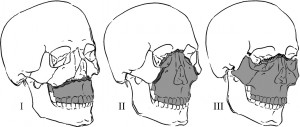

Classification

There are three types of LeFort fractures:

Le Fort I fractures (horizontal) may result from a force of injury directed low on the maxillary alveolar rim in a downward direction. It is also known as a Guerin fracture or ‘floating palate’, and usually involves the inferior nasal aperture. The fracture extends from the nasal septum to the lateral pyriform rims, travels horizontally above the teeth apices, crosses below the

zygomaticomaxillary junction, and traverses the pterygomaxillary junction to interrupt the pterygoid plates.

Le Fort II fractures (pyramidal) may result from a blow to the lower or mid maxilla and usually involve the inferior orbital rim. Such a fracture has a pyramidal shape and extends from the nasal bridge at or below the nasofrontal suture through the frontal processes of the maxilla, inferolaterally through the lacrimal bones and inferior orbital floor and rim through or near the inferior orbital foramen, and inferiorly through the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus; it then travels under the zygoma, across the pterygomaxillary fissure, and through the pterygoid plates.

Le Fort III fractures (transverse) are otherwise known as craniofacial dissociation and involve the zygomatic arch. These may follow impact to the nasal bridge or upper maxilla. These fractures start at the nasofrontal and frontomaxillary sutures and extend posteriorly along the medial wall of the orbit through the nasolacrimal groove and ethmoid bones. The thicker sphenoid bone posteriorly usually prevents continuation of the fracture into the optic canal. Instead, the fracture continues along the floor of the orbit along the inferior orbital fissure and continues superolaterally through the lateral orbital wall, through the zygomaticofrontal junction and the zygomatic arch. Intranasally, a branch of the fracture extends through the base of the perpendicular plate of the

ethmoid, through the vomer, and through the interface of the pterygoid plates to the base of the sphenoid. This type of fracture predisposes the patient to CSF rhinorrhea more commonly than the other types.

In reality, the Le Fort classification is an oversimplification of maxillary fractures. The amount of force impacted during a motor vehicle accident is much greater than Le Fort took into consideration during his work in the late 19th century. In most instances, maxillary fractures are a combination of the various Le Fort types. Fracture lines often diverge from the described pathways and may result in mixed-type fractures, unilateral fractures, or other atypical fractures. In addition, in very high-energy blows, maxillary fractures may be associated with fractures to the mandible, cranium, or both (ie, panfacial).

Two types of non–Le Fort maxillary fractures of note are relatively common. First, limited and very focused blunt trauma may result in small, isolated fracture segments. Often, a hammer or other instrument is the causative weapon. In particular, the alveolar ridge, maxillary sinus anterior wall, and nasomaxillary junction, by virtue of their accessibility, are common sites of such injury. Second, submental forces directed superiorly may result in several discrete vertical fractures through various horizontal bony supports such as the alveolar ridge, infraorbital rim, and zygomatic arches.

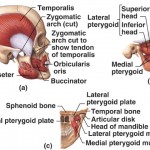

Unlike with fractures in other bones, muscle forces do not play a significant role in the final position of the broken bony segments. While several muscles attach to the maxillary framework, they typically insert to skin and therefore do not lead to additional

deformity. Instead, the basis for the patterns of maxillary fractures depends on 2 predominant factors.

First, as Le Fort described, the location, direction, and energy of the impact result in different injuries. Second, the anatomy of the mid face is oriented to provide strength and support to protect against injury. Vertical and horizontal bony bolstering in the face

absorbs the energy of traumatic force. This serves to protect the more vital intracranial contents from damage during trauma. Knowledge of the characteristics of the traumatic blow combined with an understanding of the anatomic bolstering in the face can help the clinician approach such injury in a logical and systematic fashion.

Signs and Symptoms

Lefort I – Slight swelling of the upper lip, ecchymosis is present in the buccal sulcus beneath each zygomatic arch, malocclusion, mobility of teeth. Impacted type of fractures may be almost immobile and it is only by grasping the maxillary teeth and applying little firm pressure that a characteristic grate can be felt which is diagnostic of the fracture. Percussion of upper teeth results in cracked pot sound. Guerin’s sign is present characterised by ecchymosis in the region of greater palatine vessels.

Lefort II and Lefort III (common) – gross edema of soft tissue over the middle third of the face,bilateral circumorbital

ecchymosis, bilateral subconjunctival haemorrhage, epistaxis, CSF rhinorrhoea, dish face deformity, diplopia, enophthalmos, cracked pot sound.

Lefort IIÂ – step deformity at infraorbital margin, mobile mid face, anesthesia or paresthesia of cheek.

Lefort IIIÂ – tenderness and separation at frontozygomatic suture, lengthening of face, depression of occular levels, enophthalmos, hooding of eyes, tilting of occlusal plane with gagging on one side.