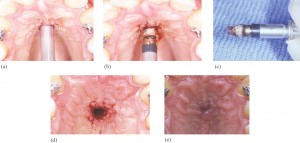

When a tooth fails to emerge through the gums, it is considered to be an impacted tooth. This commonly occurs in the case of canine teeth.

It is important to treat an impacted tooth in order to prevent the improper eruption of nearby teeth, cyst formation, possible infection or other negative changes in the jaw. Continue reading